Solving Logic Puzzles with Z3

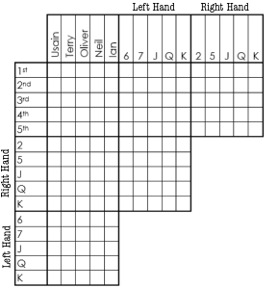

I’ve been attending Puzzled Pint events for the past year or so with a group of friends. These events are akin to pub trivia, except with puzzles, and they’re great fun. Two months ago, one of the puzzles was a classic logic grid puzzle set in a game of Texas Hold ‘Em. The organizers rated this puzzle as the most difficult that month; it took some effort, but we did solve it without hints.

At the time, I had mused about wishing for a SAT/SMT solver to do the puzzle for me. “SAT” here refers to the Boolean satisfiability problem, which is one of the classic hard problems in computer science. In turn, “SMT” is Satisfiability modulo theories, a more versatile generalization of the Boolean satisfiability problem. SAT solvers and SMT solvers both apply deduction, heuristics, and brute force to a formula to either solve it, prove that it has no solutions, or give up on it. Due to the particular way that both the SAT problem and SMT problem are hard, there’s no general way to efficiently solve every formula, but modern solvers can get answers on a lot of practical problems. But what of problems with no practical application?

Later in the week, after Puzzled Pint, I sat down and re-solved the poker logic puzzle using Z3, an open source and freely available SMT solver by Microsoft. I’ve enjoyed playing around with Z3, and it’s the sort of hammer that can make everything look like a nail. Z3 uses an internal language that looks a lot like a LISP, which I’m given to understand is typical in the field. I used Z3’s Python library, which makes it easy to build Z3 expressions using function calls and normal mathematical operators.

Due to terminology differences between fields, Z3 uses the term “constant” instead of “variable” to refer to symbols like x and y in the formula 4 * x + 3 * y = 27. Also, Z3 uses the term “sort” to describe what kind of value each constant can hold. To model the problem statement, I used IntSort to track the order in which the players folded, and I defined new EnumSorts for non-numerical values like names. To tie the different values together, I defined functions that mapped player names to the values of their other properties. With this scaffolding in place, I translated each puzzle clue into constraint formulas, adding a new constant each time a clue mentioned an unknown player. I then ran the solver, printed out the results, added one more constraint to rule out that particular solution, and ran the solver again to confirm that the solution was unique.

I have posted the logic puzzle solver script in a gist, along with scripts for two more similar puzzles from other sources. Each script finds the answer in well under a second. To run these scripts, you’ll need Python 3 and the z3-python package installed. The same ideas should work on any logic puzzle, as long as the constraint formulas capture the precise meaning of each clue. Enjoy!